Developing Real-Time Computer Vision Applications for Intel Pentium III based Windows NT Workstations

Ross Cutler and Larry Davis

September 4, 1999

http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/pub/frame99

1.1††††† What is a real-time application?

1.2††††† Why Intel Pentium III PCs?

2†††† Overview of a Real-Time Computer

Vision Application

3.1††††† Capturing video for offline use

4†††† Optimizing your application

4.1††††† The Pentium III PC architecture

4.2††††† Benchmarking the memory system

4.3††††† How to detect memory bottlenecks

4.4††††† What is the upper limit on how fast my

algorithm will run?

4.5††††† Using MMX and Streaming SIMD

4.6††††† Memory alignment issues

4.7††††† Managing the L1/L2 cache

4.8††††† Utilizing multiple CPUs

4.8.3†††††† Cache issues with SMP systems

4.9††††† Benchmarking your application

4.10††† Bypassing Windows NTís virtual memory system

4.12††† Hardware acceleration of image processing

operations

5†††† Sample vision application

6†††† Hard real-time extensions to Windows

NT

Abstract

In this paper, we describe our experiences in developing real-time computer vision applications for Intel Pentium III based Windows NT workstations.† Specifically, we discuss how to optimize your code, efficiently utilize memory and the file system, utilize multiple CPUs, get video input, and benchmark your code.† Intrinsic soft real-time features of Windows NT are discussed, as well as hard real-time extensions. An optimized real-time optical flow application is given. Empirical results of memory subsystems and cache scheduling issues are also reported.

1 Introduction

Intel processor-based PCs running the Microsoft Windows 98/NT operating systems are the clear market leader in both home and business computer use.† Utilizing the ubiquitous PC for the use in real-time computer vision applications is appealing for both the user and developer.† For the user, utilizing their existing inexpensive hardware and operating system is attractive for both economical and integration reasons.† For the developer, the success of the PC has produced many useful developer tools and hardware peripherals that can be utilized for developing a real-time computer vision application.† However, effectively utilizing the power of this hardware requires a great deal of low-level understanding of the hardware and low-level programming, which this paper attempts to address.

1.1 † What is a real-time application?

A real-time application is one that can respond in a predictable, timely way to external events.† Real-time system requirements are typically classified as hard or soft real-time.† For a hard real-time system, events must be handled predictably in all cases; a late response can cause a catastrophic failure.† For a soft real-time system, not all events must be handled predictably; some late responses are tolerated.† For many real-time computer vision applications, a soft real-time system is sufficient.† For example, in a real-time gesture recognition system (e.g., [1]), it may be tolerable to occasionally or systematically drop video frames, as long as the system is designed to robustly handle frame drops

1.2 Why Intel Pentium III PCs?

The recent Intel Pentium III processor now provides sufficient processing power for many real-time computer vision applications.† In particular, the Pentium III includes integer and floating point Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions, which can greatly increase the speed of computer vision algorithms.† Multiprocessor Pentium III systems are relatively inexpensive, and provide similar memory bandwidths and computational power as non-Intel workstation costing significantly more money.

The reference PC used in all of the benchmarks given in this paper is a Dell 610 dual 550 MHz Pentium III Xeon, with 512 MB of ECC SDRAM.

1.3 Why Windows NT?

We utilize the Microsoft Windows NT operating system for our real-time computer vision application development.† The reasons for choosing Windows NT over the more popular Windows 98 are: (1) Windows NT supports multiple processors; (2) Windows NT has a better architecture for real-time applications than Windows 98; (3) Windows NT is more robust than Windows 98.† The reason for choosing Windows NT over Linux is that Windows NT provides many software development tools that arenít available on Linux.† In addition, Windows NT has a superior number of hardware peripherals available (with supported drivers), particularly for frame grabbers (essential for most real-time vision applications).

Windows NT is a general-purpose operating system, and was designed to maximize aggregate throughput and achieve fair sharing of resources.† It was not designed to provide low-latency responses to events, predictable time-based scheduling, or explicit resource allocation mechanisms. Real-time OS features not found in Windows NT include deadline-based scheduling, explicit CPU or resource management, priority inheritance, fine-granularity clock and timer services, and bounded response times for essential system services.† However, real-time OS features Windows NT does include are elevated fixed real-time thread priorities, interrupt routines that typically re-enable interrupts very quickly, and periodic callback routines [2-4].

1.4 Contributions

This paper serves three purposes.† First, it summarizes many of the important issues in developing real-time applications on a Windows NT Intel Pentium III platform, including many references for further details.† In addition, we provide empirical results of memory and cache scheduling issues, which are particularly important for real-time computer vision applications.† Finally, we give working examples of computer vision algorithms, which can be further used for building real-time computer vision applications.

2 Overview of a Real-Time Computer Vision Application

A typical real-time

computer vision system includes the following components:

Figure 1:

Real-time computer vision system components

The video input is typically a CCD-based video camera, connected to a frame-grabber installed in the PC (see Section 3).† The image and computer vision processing can be done by the main CPU(s), by the graphics hardware (see Section 4.12), and by optional digital signal processors (DSPs) (e.g., a C80 integrated on the video capture card).† The processing of results depends completely on the application.† For example, a real-time person tracker may send tracking events to another process running on the system, which displays the results in real-time using a graphical user interface (GUI).

3 Video input

Capturing live video is an essential part of most real-time computer vision applications.† Windows NT 4.0 provides the Video For Windows (VFW) [5] interface as a standard for video input.† While VFW may suffice for some applications, it has some efficiency problems.† Specifically, VFW drivers perform memory copies on the captured images, instead of transferring images directly to DMA image buffers and making these buffers available to the user.† The result of this inefficiency is wasted CPUs cycles and dropped frames during video captures.

In Windows 2000 (and Windows 98), VFW is succeeded by WDM Video Capture [5], which alleviates many of the problems of VFW.† In WDM Video Capture, images are transferred directly to a circular DMA buffer, and user interrupts are triggered when an image capture completes.† WDM Video Capture uses the DirectShow interface to provide compatibility with many third-party applications.

There are numerous (over 30 at last count) PCI-based machine vision frame grabbers available for Intel-based Windows NT workstations.† Almost all of these frame grabbers provide a custom SDK, which the programmer can use for direct control of the frame grabber.† Many of the machine vision (not consumer) frame grabbers do not support VFW, due to the inadequacies previously discussed.†

A common paradigm used for providing live video is to capture the video in a circular image buffer, and trigger the consumer of the video images when a new frame is ready (typically via a callback function).† The image buffers are DMA buffers, which the frame grabber can write directly to, and which the user can process directly without memory copies.† The size of the circular buffer depends on how much image history is required for the application, and how quickly the images can be processed.† For example, if only the current frame is required, and the processing can always finish in less than the frame-sampling interval (e.g., 33ms for NTSC video), then a circular buffer length of 2 suffices (this is called double-buffering).† However, since Windows NT is not hard real-time, one should not assume that the processing can always finish on time.† Instead, a larger circular buffer length should be used to account to the variability in the processing time.

The Microsoft Vision SDK (http://www.research.microsoft.com/projects/VisSDK) provides a useful abstraction for device independent capturing video, which we use in our own development.

3.1 Capturing video for offline use

Capturing video for offline use is an essential task in developing a computer vision application.† Computer vision algorithms can be deterministically tested and optimized using the captured video.† Video can be captured to memory or disk.†

When capturing to disk, a RAID is typically used to provide sufficient throughput.† For example, a 640x480x24 image sequence at 30 fps requires 26.4 MB/s sustained disk throughput, which can be achieved using two fast SCSI disks (e.g., Seagate Ultra 2 Wide SCSI Cheetah disks).† A RAID controller is not required, as Windows NT can efficiently simulate a level-0 RAID in software.† To maximize throughput, we bypass the Windows NT file cache, which would otherwise copy the streaming image data to virtual memory; even worse, the default settings for the file cache cause the file cache to grow until the system starts to swap!† Multiple file DMA buffers (typically 4) and overlapped writes are used to account for the disk throughput variations. The image file is pre-allocated to allow overlapped writes to execute optimally.† See [6] for details and source code.† See [7] for a useful disk benchmarking utility.† See http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/software for other video capture applications.

When capturing to memory, it is most efficient (space-wise) to capture to memory above what Windows NT uses (see Section 4.10).† Otherwise, Windows NT 4.0 can only utilize 40% of the DMA buffers actually requested.† Some of the available frame grabber drivers (e.g., from Matrox and EPIX) provide direct support for image buffers above the Windows NT memory space, so that 100% of the memory can be utilized for image buffers (less the amount used by Windows NT).†

4 Optimizing your application

Because of the massive amounts of data involved, computer vision algorithms can be extremely computationally expensive.† In order to make this processing run in real-time, often a great deal of optimization needs to be utilized.† The payoff in doing so can be significant: we have increased the speed of many computer vision algorithms by over 10 times by utilizing the techniques described in this section.

4.1 The Pentium III PC architecture

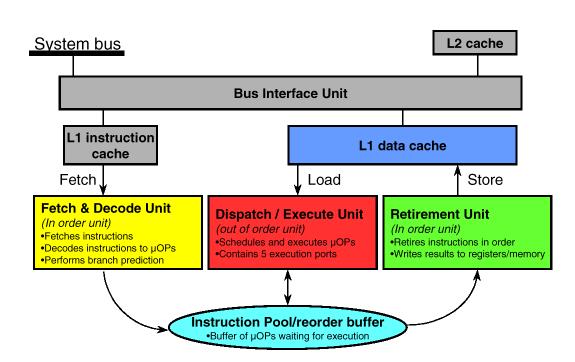

The Pentium III is a general purpose 32-bit CPU, with some DSP-like features added to accelerate multimedia applications.† The DSP-like features include integer and floating point SIMD instructions, as well as cache control.† A block diagram of a dual Pentium III Xeon system is given in Figure 2 [8].† A block diagram of the Pentium III is given in Figure 3 [9].† The Pentium III consists of three major units: Fetch and decode; dispatch / execute; and retirement.† The dispatch / execute (DE) unit is detailed in Figure 4.† On each clock cycle, the DE unit can send a micro-op to each the 5 ports.† With careful coding, the Pentium III can execute instructions on multiple ports simultaneously.

Figure 2: Dual Pentium III system block diagram [8]

Figure 3: Pentium III Architecture [9]

Figure 4: Execution Units and Ports in the Out-Of-Order Core [9]

4.2 Benchmarking the memory system

Many computer vision algorithms can be memory-bound if not properly designed and coded (i.e., the processor spends excessive time waiting on the memory to read/write data).† To avoid these situations, we need to fully understand the design and actual throughput of the memory system.† The memory system of a Pentium III Xeon PC consists of a 32 KB L1 cache (16 KB data, 16 KB code, four-way set associative with a cache line length of 32 bytes, pseudo-least recently used replacement algorithm), a 512KB L2 cache (larger L2 caches are available), and ECC SDRAM main memory.† The theoretical and actual speeds of these memory subsystems are given in Table 1.† The theoretical speeds are for either memory reads or writes.† The memcpy() and fastcopy() speeds are for read plus writes.† Note that the Pentium III (non-Xeon) has an L2 cache that is half the speed of the Pentium III Xeon.

|

|

Theoretical |

memcpy |

fastcopy |

readmem128 |

readmem64 |

Writemem128 |

writemem64_movq |

|

L1 cache |

4400 |

2196 |

513 |

3653 |

1779 |

723 |

1338 |

|

L2 cache |

4400 |

400 |

385 |

2177 |

1755 |

727 |

492 |

|

Main |

800 |

164 |

393 |

590 |

547 |

730 |

264 |

Table 1: Theoretical and actual memory subsystem speeds (in MB/s) of a 550 MHz Pentium III Xeon

The main memory uses SDRAM (PC-100) with a 100 MHz 64-bit wide simplex bus, with a theoretical limit of 800 MB/s (or 400 MB/s for copies).† Our fastcopy() benchmark gave an actual speed of 393 MB/s (read plus write).† Note this is over twice the main memory performance of comparable workstations like the SGI Octane (see the STREAM benchmark, http://www.cs.virginia.edu/stream).† (Note that the STREAM memory copy benchmarks report twice the throughput actually achieved; our 393 MB/s result for fastcopy() would be reported as 786 MB/s by STREAM).

To benchmark the memory subsystem, we measure the time it takes to copy (both read and write) a source buffer to a destination buffer, for various buffer sizes.† We repeat each copy many times to ensure the memory is totally within the cache, if the buffer is small enough.† The main memory speed can be measured using a buffer that canít fit within the cache (thus ensuring caches misses for every byte copied).† The source code used in benchmarking the memory subsystems is at http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/pub/frame99/BenchMemory.zip.

The standard memcpy() function uses the rep movsb instruction to copy a block of memory from a source to destination.† This method can be improved with the Pentium III by using the 128-bit Streaming SIMD registers and prefetching the cache [9].† Specifically, we first read a byte from the source buffer to ensure that the memory page that the buffer resides in is in the transaction lookaside buffer (TLB), since prefetches only work for memory pages within the TLB.† We then prefetch 4 KB of memory into the L1 cache, and then copy 4KB of memory using 128-registers.† The actual copy is unrolled twice to improve performance.† The code is given below in the function fastcopy().† Note that fastcopy() is significantly faster than memcpy() for main memory copies (see Table 1).† One caveat of fastcopy() is that the memory copied will not reside in the L2 cache, since the L2 cache is bypassed during the memory copy.† Therefore, subsequent operations on the source or destination data may not generate a L2 cache hit, as it might with memcpy().

#define CACHESIZE 4096

#define CACHELINESIZE 32

// copy memory from source to dest

using 128-bit Streaming SIMD registers

// assumes: n >= CACHESIZE

void fastcopy(char *dest, char *source,

int n)

{

††††††† for

(int i=0; i < n; i+=CACHESIZE) {

†††††††††††††††††††††† char

temp = source[i+CACHESIZE];

†††††††††††††††††††††† for

(int j=i+CACHELINESIZE; j<i+CACHESIZE; j+=CACHELINESIZE) {

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† _mm_prefetch(source+j,

_MM_HINT_NTA);

†††††††††††††††††††††† }

†††††††††††††††††††††† for

(j=i; j<i+CACHESIZE; j+=32) {

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† _mm_stream_ps((float*)(dest+j),

_mm_load_ps((float*)(source+j)));

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† _mm_stream_ps((float*)(dest+j+16),

_mm_load_ps((float*)(source+j+16)));

†††††††††††††††††††††† }

††††††† }

†††††††† _mm_sfence();

}

In order to benchmark reading memory, we read memory directly to a 128-bit Streaming SIMD register.† The code is given in readmem128() below.† We found that unrolling the read did not improve performance.

// read memory into a 128-bit Streaming

SIMD register

void readmem128(char *source, int n)

{

††††††† int

n2 = n / 16;

††††††† _asm

{

†††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† ecx, n2

†††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† edx, 0

†††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† esi, source

loop1:

†††††††††††††††††††††† movaps†††††††††††††††† xmm0, [esi+edx]

†††††††††††††††††††††† add††††††††††††††††††††††† edx, 16

†††††††††††††††††††††† dec††††††††††††††††††††††† ecx

†††††††††††††††††††††† jne†††††††††††††††††††††††† loop1

††††††† }

}

We also benchmark reading memory by using the 64-bit MMX registers.† The code is given in readmem64() below.† We found that unrolling the read twice improved the read performance by 16% over the unrolled version.

// read memory into a 64-bit MMX register

// unrolled read twice

void readmem64(char *source, int n)

{

int n2 = n / 16;

_asm {

mov††††††††††††††† ecx, n2

†††††††††††††† mov††††††††††††††† edx, 0

mov††††††††††††††† esi, source

loop1:

†††††††††††††† movq††††††††††††† mm0, [esi+edx]

†††††††††††††† movq††††††††††††† mm1, [esi+edx+8]

†††††††††††††† add†††††††††††††††† edx, 16

†††††††††††††† dec†††††††††††††††† ecx

†††††††††††††† jne††††††††††††††††† loop1

†††††††††††††† emms

}

}

To benchmark writing memory, we write to memory from a 128-bit Streaming SIMD register.†† We bypass the L1 and L2 cache by using the movntps streaming store instruction.† This technique gives 91.2% of the theoretical maximum write speed of 800 MB/s in the tested system.† The code is given in writemem128() below.

// write to memory from a 128-bit Streaming SIMD register

void writemem128(char *dest, int n)

{

int n2 = n / 16;

_asm {

†††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† ecx, n2

†††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† edx, 0

†††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† edi, dest

loop1:

†††††††††††††† movntps††††††††††††††† [edi+edx], xmm0

†††††††††††††† add††††††††††††††††††††††† edx, 16

†††††††††††††† dec††††††††††††††††††††††† ecx

†††††††††††††† jne†††††††††††††††††††††††† loop1

}

}

We also benchmark writing memory from a 64-bit MMX register.† We bypass the L1 and L2 cache by using the movntps streaming store instruction.† This technique gives 90.6% of the theoretical maximum write speed of 800 MB/s in the tested system.† The code is given in writemem128() below.

// write to memory from a 64-bit MMX register

void writemem64(char *dest, int n)

{

††††††† int n2 = n / 8;

††††††† _asm {

†††††††††††††† mov††††††††††††††† ecx, n2

†††††††††††††† mov††††††††††††††† edx, 0

†††††††††††††† mov††††††††††††††† edi, dest

loop1:

†††††††††††††† movntq†††††††††† [edi+edx], mm0

†††††††††††††† add†††††††††††††††† edx, 8

†††††††††††††† dec†††††††††††††††† ecx

†††††††††††††† jne††††††††††††††††† loop1

†††††††††††††† emms

††††††† }

}

We do a similar memory write benchmark using the 64-bit MMX register, but without using a streaming store.† The results are 2.75 times slower than when writing with the streaming store.† The code is given in writemem64_movq() below.

// write to memory from a 64-bit MMX register

void writemem64_movq(char *dest, int n)

{

int n2 = n / 8;

_asm {

†††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† ecx, n2

†††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† edx, 0

†††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† edi, dest

loop1:

†††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† [edi+edx], mm0

†††††††††††††† add††††††††††††††††††††††† edx, 8

†††††††††††††† dec††††††††††††††††††††††† ecx

†††††††††††††† jne†††††††††††††††††††††††† loop1

†††††††††††††† emms

}

}

A plot of the output for all of these benchmarks is shown in Figure 5.† This plot clearly shows the three levels of memory speeds in this PC.† This plot be used to infer the size of the L1 and L2 cache, since the memory speed changes dramatically once the source plus destination buffer size equals the cache size (shown here at 16KB and 512KB for the readmem() results).† The reason the for the slow taper at the buffer size of 512 KB to about 633 KB is that the L1 and L2 cache are still being used.†

Figure 5: Memory benchmark results

4.3 How to detect memory bottlenecks

As mentioned in the previous section, memory throughput can be a significant bottleneck on computer vision algorithms.† To determine whether this is the case in your algorithm, you can modify your code and insert timing instructions, or you can utilize the performance monitoring events on the Pentium III with a performance analysis tool like VTune [10].

The first technique is simple to apply for algorithms that read memory, process it, and write the results (e.g., an image filter).† One can first benchmark the unmodified algorithm (see Section 4.9), and then benchmark the algorithm after eliminating the writing of results.† If possible, do the same for the memory read, possibly using fake data (e.g., an image of zeros, generated with no memory reads).

For more complicated algorithms, the performance monitoring events on the Pentium III can also yield useful results [10].† Specifically, the Pentium III has events to monitor the number of L1 and L2 caches hits, as well as the number of memory accesses.† This information can be used to determine if the memory system is being used efficiently, and how much the processor is waiting for memory operations to complete.

4.4 What is the upper limit on how fast my algorithm will run?

The Streaming SIMD instructions can perform 4 single precision floating point operations every 2 cycles.†† Since the adder and multiplier floating point units can operate simultaneously, this results in 2200 MFLOPS on a 550MHz Pentium III [9].† Since each floating point number is 4 bytes, this corresponds to 17,600 MB/s of required data throughput (read plus write), clearly higher than the actual memory speeds that the Pentium III provides.† Similarly, the Pentium III can perform 4 16-bit integer arithmetic operations every cycle.† This corresponds to 2200 MIPS, or 8800 MB/s of data throughput.† Obviously, in order to obtain close to the theoretical performance, you must try to keep the data youíre processing in registers or the L1 or L2 cache, since the main memory is far too slow for the required throughput.

One can use these best-case estimates of computational power to estimate the upper limit speed on a particular algorithm.† In most cases, the best-case estimates will never be achieved, due to the memory bottlenecks and other processor contentions.† However, such an estimate is still useful as a guideline of how optimized your code is.

4.5 Using MMX and Streaming SIMD

The Pentium III includes MMX instructions and eight 64-bit registers for performing integer SIMD operations, and Streaming SIMD instructions and eight 128-bit registers for performing floating point SIMD operations.† To utilize the MMX and Streaming SIMD features of the Pentium III, there are several options:

- inline assembly instructions on the Intel C++ compiler (Visual C++ 6.0 only supports MMX inline assembly instructions)

- MMX and Streaming SIMD intrinsics with the Intel C++ compiler

- Intel C++ Class Libraries for SIMD operations

- Intel C++ compiler, with vectorization enabled

- Intel Performance Libraries

There are many Intel Application Notes for both MMX (http://www.intel.com/drg/mmx/appnotes) and Streaming SIMD (http://developer.intel.com/vtune/cbts/strmsimd/appnotes.htm), which provide in-depth examples of common applications.

As an example of using inline MMX instructions, the following function scales an imageís pixel values by a fractional factor.† This function runs 11 times faster than a C version on the same PC.† One application of this function is to normalize an image to account for automatic gain control [11].

void imageScaleMMX(unsigned char *image, int x, int width, int height)

/*

Description:

†††††††† Scale the image by x/64.

Arguments:

†††††††† image -- image data pointer to scale

†††††††† x -- x/64 is ratio to scale with

†††††††† width, height -- image size

Author:

†††††††† Ross Cutler

*/

{

†††††††† int n = width * height;

†††††††† assert(n % 8 == 0);

†††††††† n = n >> 3;

†††††††† __asm {

††††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† esi, image

††††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† ecx, n

††††††††††††††††††††††† movd†††††††††††††††††††† mm4, x†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm4 = [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 x]

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm3, mm4††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm3 = [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 x]††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††† psllq†††††††††††††††††††††† mm3, 16†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm3 = [0 0 0 0 0 x 0 0]

††††††††††††††††††††††† por†††††††††††††††††††††††† mm4, mm3††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm4 = [0 0 0 0 0 x 0 x]

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm3, mm4††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm3 = [0 0 0 0 0 x 0 x]††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††† psllq†††††††††††††††††††††† mm3, 32†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm3 = [0 x 0 x 0 0 0 0]

††††††††††††††††††††††† por†††††††††††††††††††††††† mm4, mm3††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm4 = [0 x 0 x 0 x 0 x]

††††††††††††††††††††††† pxor†††††††††††††††††††††† mm7, mm7††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm7 = 0

loop1:

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm0, [esi]††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm0 = [p7 p6 p5 p4 p3 p2 p1 p0]

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm1, mm0††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm1 = [p7 p6 p5 p4 p3 p2 p1 p0]

††††††††††††††††††††††† punpckhbw††††††††††† mm0, mm7††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm0 = [0 p7 0 p6 0 p5 0 p4]

††††††††††††††††††††††† punpcklbw†††††††††††† mm1, mm7††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm1 = [0 p3 0 p2 0 p1 0 p0]

††††††††††††††††††††††† pmullw†††††††††††††††††† mm0, mm4††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm0 = [p7*x p6*x p5*x p4*x]

††††††††††††††††††††††† pmullw†††††††††††††††††† mm1, mm4††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm1 = [p3*x p2*x p1*x p0*x]

††††††††††††††††††††††† psrlw†††††††††††††††††††† mm0, 6†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm0 = [p7*x/64 p6*x/64 p5*x/64 p4*x/64]

††††††††††††††††††††††† psrlw†††††††††††††††††††† mm1, 6†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm1 = [p3*x/64 p2*x/64 p1*x/64 p0*x/64]

††††††††††††††††††††††† packuswb††††††††††††† mm1, mm0††††††††††††††††††††††††† // mm1 = [r7 r6 r5 r4 r3 r2 r1 r0], r is result

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† [esi], mm1

††††††††††††††††††††††† add††††††††††††††††††††††† esi, 8

††††††††††††††††††††††† dec††††††††††††††††††††††† ecx

††††††††††††††††††††††† jnz†††††††††††††††††††††††† loop1

††††††††††††††††††††††† emms

†††††††† }

}

4.6 Memory alignment issues

The Pentium III memory movement instructions (e.g., mov, movd, movq) have a significant performance penalty if used with memory addresses that are not properly aligned [9].† Memory addresses should be a multiple of 4 when utilizing 32-bit registers, a multiple of 8 with utilizing 64-registers, and a multiple of 16 when utilizing 128-bit registers.†† Indeed, some of the Streaming SIMD instructions (e.g., movaps) invoke an exception when used with an address that is not 16 byte aligned.† For methods on how to align your data within the Visual C++ and Intel C++ compilers, see [12], [13].

4.7 Managing the L1/L2 cache

As shown in Section 4.2, the L1 and L2 cache are significantly faster than main memory, and utilizing the cache effectively is essential in achieving optimal performance.† The Pentium III includes instructions to help manage the cache.† Specifically, there are instructions to prefetch data into the L1, L2, or both, before the data is actually used (prefetch0, prefetcht1, prefetcht2, prefetchnta).† The prefetch instructions can help minimize the latencies of data accesses.

There are also instructions to move memory directly from 64 and 128 bit registers to main memory without going through the cache (movntq, movntps).† This is useful to store data that will not be used soon (non-temporal data), thus preserving the contents of the L1 and L2 cache.† In addition, the writemem64() example in Section 4.2 showed that writes bypassing the cache have a significantly higher bandwidth than when using the cache (though the latency for a single write is longer when bypassing the cache).

Finally, the sfence instruction enforces strong ordering and cache coherency for weakly-ordered memory accesses.† Specifically, the sfence instruction ensures that the data of any store instruction in a program that precedes an sfence instruction is written to memory before any subsequent store instruction.

4.8 Utilizing multiple CPUs

One method to increase the speed of an application is to utilize more than one CPU.† For example, dual-processor Pentium III workstations provide a symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) architecture that can double the speed of many vision applications compared to a similar uniprocessor Pentium III workstation.†

4.8.1 Threads

In a SMP workstation, Windows NT schedules threads in the ready queue to the first available processor (subject to thread processor affinities Ė see Section 4.8.3).† To utilize multiple processors, your application must use multiple processes, threads or fibers (see Section 4.8.2).† For example, if you have two images to process within an applicationís process, a thread can be assigned to each processor to perform this.† The following code shows an example of this:

#define WIDTH 640

#define HEIGHT 480

CEvent thread1done;

UINT thread1(void *p) {

†††††††† processImage((char *)p);

†††††††† thread1done.SetEvent();

}

CEvent thread2done;

UINT thread2(void *p) {

†††††††† processImage ((char *)p);

†††††††† thread2done.SetEvent();

}

main() {

†††††††† char image1[WIDTH][HEIGHT], image2[WIDTH][HEIGHT];

†††††††† // Ö

†††††††† // start two threads to process images, and wait for completion

AfxBeginThread(thread1, image1, THREAD_PRIORITY_NORMAL);

AfxBeginThread(thread2, image2, THREAD_PRIORITY_NORMAL);

†††††† ::WaitForSingleObject(thread1done, INFINITE);

†††††† ::WaitForSingleObject(thread2done, INFINITE);

}

In this code, we start two threads within the current process, thread1() and thread2(), and wait for their completion using events (a method NT provides for intra-process synchronization).† Threads have a scheduling priority assigned to them, which specified by the priority class of its process (e.g., REALTIME_PRIORITY_CLASS), and a priority level within that class (e.g., THREAD_PRIORITY_NORMAL).† For real-time applications, you typically want a priority class of REALTIME_PRIORITY_CLASS or HIGH_PRIORITY_CLASS to prevent your process from being preempted by a ďless importantĒ process.† Note that with a REALTIME_PRIORITY_CLASS priority process, the process has greater priority than the Windows desktop.† Care must be taken when developing such a process, since an infinite loop within the process will lock the Windows desktop, requiring a reboot of the system (unless debugging is done remotely using another PC, in which the offending process can be terminated).

4.8.2 Fibers

A fiber is a unit of execution that must be manually scheduled by the application.† Fibers can be useful for real-time applications which require explicit scheduling.† See [5] for details on the use of fibers.

4.8.3 Cache issues with SMP systems

In a SMP Pentium III system, each processor has its own L1 and L2 cache, and shares a common main memory (see Figure 2).† When a thread is first started, it is assigned an ideal processor to run on, based on the current processor load (the ideal processor can be explicitly set using the SetThreadIdealProcessor() function).† The NT scheduler will try to schedule that thread on the ideal processor when it is available.† In order to force the scheduler to always use a desired processor (in order to obtain optimal cache hits) the Win32 function SetThreadAffinityMask() can be used.† The performance benefit of doing so can be significant, as shown in Table 2.† In this example, we have two threads repeatedly processing two images (a simple in-place image filter).† In the worst case scheduling, a thread is assigned to a different processor for each image to process.† This ensures that the L1 and L2 cache will not get any hits on the image.† When thread affinity is used, the best-case scheduling is given, and the L1 and L2 cache get many hits.† The result is that when thread processor affinity is used, the process runs 2.9 times faster than when it isnít used and gets the worst case scheduling.† The source code for this benchmark is given in http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/pub/frame99/BenchProcessorAffinity.zip.

|

|

Execution

time |

|

Thread

affinity |

283

ms |

|

Worst-case

scheduling |

830 ms |

Table 2:

Performance effects of processor affinity

4.9 Benchmarking your application

In order to determine which parts of your system need to be optimized, you need to benchmark your system.† All Pentium CPUs include a 64-bit timing register, which gives a count of the number of clock ticks.† A 550 MHz system has a 1.82 nanosecond clock interval, which is more than sufficient to provide accurate benchmarks.† A C++ class that uses this register is given in Section 4.9.1.

4.9.1 Timer class

The Win32 API provides the QueryPerformanceCounter() and QueryPerformanceFrequency() functions to access the timing register count and frequency described in the previous section.† The C++ Timer class given below can be readily used to benchmark components of your system.† In using this Timer class, note that the actual time returned is wall-clock time, not actual CPU usage time.† Therefore, in order to maximize the benchmarking accuracy, make the priority of the process REALTIME_PRIORITY_CLASS, so that other unrelated tasks donít get scheduled during the benchmarking.† There is still the possibility of interrupts getting triggered while benchmarking, so while benchmarking, ensure that all other system activity (e.g., network, mouse, graphics) is minimized.† Jones and Regehr [2] provide some interesting examples of how other system activity can directly affect the real-time performance of NT.

class

Timer {

private:

†††††††††††††† LARGE_INTEGER startTime,

stopTime;

†††††††††††††† LARGE_INTEGER freq;

public:

†††††††††††††† Timer() {

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† QueryPerformanceFrequency(&freq);

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† startTime.LowPart

= startTime.HighPart = 0;

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† stopTime.LowPart =

stopTime.HighPart = 0;

†††††††††††††† }

†††††††††††††† // start the timer

†††††††††††††† void start() {

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† QueryPerformanceCounter(&startTime);

†††††††††††††† }

†††††††††††††† // stop the timer

†††††††††††††† void stop() {

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† QueryPerformanceCounter(&stopTime);

†††††††††††††† }

†††††††††††††† // returns the duration of the

timer (in seconds)

†††††††††††††† double duration() {

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† return

(double)(stopTime.QuadPart - startTime.QuadPart) / freq.QuadPart;

†††††††††††††† }

};

4.9.2 VTune

Another useful tool in benchmarking a system is Intelís VTune 4.0 [10].† VTune can be used to perform both static and dynamic code analysis, and sampling-based analysis.† The static and dynamic code analysis is useful for detecting assembly instructions that cause severe bottlenecks (e.g., processor stalls).† The sampling-based analysis instruments your code and uses a sampling technique to determine the hot spots in your system (e.g., where the most time is being used).† This technique is useful for detecting bottlenecks that the static analysis cannot predict (e.g., cache misses), as well as showing the overall PC usage (i.e., the OS, including drivers, are also sampled during the dynamic analysis).†

4.10 Bypassing Windows NTís virtual memory system

Windows NT includes a boot option, /maxmem, which specifies the maximum amount of memory NT is allowed to use.† This boot option is specified in the c:\boot.ini file; for example, the following line limits Windows NT to using 128MB of RAM.

multi(0)disk(0)rdisk(0)partition(1)\WINNT="Windows NT 4.0 [128]" /maxmem=128

When this boot configuration is selected at boot-time, Windows NT will use the first (starting from address 0) 128MB of memory.† The memory above 128MB is available for any driver to utilize.† For example, a frame grabber driver can utilize this non-NT memory for storing images, without the 60% DMA space overhead imposed within Windows NT drivers (frame grabbers by Matrox and EPIX utilize this).† Developers can also utilize this memory via the memio example driver given in the Windows DDK.† The primary advantage of using this upper memory instead of user-memory is that it is not virtual, and thus not swappable, which provides more deterministic scheduling for processing of large data sets.

4.11 Code optimization

In this section, we will provide suggestions and references

on how to further optimize your code.†

Perhaps the simplest technique is to utilize an optimizing compiler,

such as the Intel C++ compiler (http://developer.intel.com/vtune/icl).† The Intel C++ compiler is highly optimized

for the Pentium architecture, and in many of our test cases produced superior

code than the Microsoft Visual C++ compiler.†

In addition, the Intel C++ compiler includes MMX and Streaming SIMD

intrinsics and C++ classes to ease the use of MMX and Streaming SIMD.† The Intel C++ compiler can also vectorize

simple loops containing arithmetic instructions on arrays.

†††††† The Intel Performance Libraries, http://developer.intel.com/vtune/perflibst/index.htm, provides a set of libraries that are optimized for the Pentium processors.† Of particular use is the Intel Image Processing Library, which includes many low-level image processing functions.† A related library is the Intel Small Matrix Library, http://developer.intel.com/design/PentiumIII/sml, which is a C++ single precession matrix library optimized for the Pentium III.

†††††† For more information on optimizing your code, see [9, 14, 15], as well as the interactive Intel Architecture Tutorials, http://developer.intel.com/vtune/cbts/cbts.htm.

4.12 Hardware acceleration of image processing operations

The graphics hardware can be used to accelerate certain

image processing operations, such as image resizing and warping.† For this to be effective, you must have a

high-end graphics adapter installed in your PC, which includes hardware

acceleration for the desired operations.†

There are two common graphics libraries uses for Windows, Direct3D and

OpenGL. Direct3D is not available for Windows NT 4.0, but is available on

Windows 98 and 2000.† Both libraries

support rendering to off-screen buffers, which is how to utilize the graphics

hardware to accelerate the image processing.†

Within Direct3D, use the CreateOffScreenSurface()

to create an off-screen surface.† Within

OpenGL, off-screen rendering can be performed using GLXPixmaps.

5 Sample vision application

In this section we provide a sample application to compute real-time optical flow.† The flow algorithm we utilize is correlation-based, using color video images to enhance the correspondence accuracy.† To speed up the flow estimation, we use a 1D search pattern and only estimate the flow in regions where motion is detected (see [1] for details).† We use the Pentium III correlation instruction psadbw for computing the absolute correlation of 4x4 RGBA patches, which is the core part of the algorithm; the code is given below:

inline int computeSAD4x4RGBAMMX2(unsigned char *image1, unsigned char *image2, int rowWidth)

/*

Description:

†††††††† Compute the SAD of the 4x4 patch in image 1 with upper left corner at image1 w.r.t. image 2 at image2.

Arguments:

†††††††† image1, image2 -- image patches to compute SAD with

†††††††† rowWidth -- in bytes

Author:

†††††††† Ross Cutler

*/

{

†††††††† int sum;

†††††††† __asm {

††††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† edi, image1

††††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† esi, image2

††††††††††††††††††††††† mov†††††††††††††††††††††† ecx, 4†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // do 4 rows

††††††††††††††††††††††† pxor†††††††††††††††††††††† mm4, mm4

row_loop:

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm0, [edi]††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // grab 1st half of patch row from image 1

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm1, [esi]††††††††††††††††††††††††††† // grab 1st half of patch row from image 2

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm2, [edi+8]††††††††††††††††††††††† // grab 2nd half of patch row from image 1

††††††††††††††††††††††† movq†††††††††††††††††††† mm3, [esi+8]††††††††††††††††††††††† // grab 2nd half of patch row from image 2

††††††††††††††††††††††† add††††††††††††††††††††††† esi, rowWidth†††††††††††††††††††††† // move to next row

††††††††††††††††††††††† add††††††††††††††††††††††† edi, rowWidth†††††††††††††††††††††† // move to next row

††††††††††††††††††††††† psadbw†††††††††††††††† mm0, mm1

††††††††††††††††††††††† psadbw†††††††††††††††† mm2, mm3

††††††††††††††††††††††† paddw†††††††††††††††††† mm0, mm2††††††††††††††††††††††††† // accumulate difference...

††††††††††††††††††††††† paddw†††††††††††††††††† mm4, mm0

††††††††††††††††††††††† dec††††††††††††††††††††††† ecx

††††††††††††††††††††††† jnz†††††††††††††††††††††††† row_loop

††††††††††††††††††††††† movd†††††††††††††††††††† sum, mm4

†††††††† }

†††††††† return sum;

}

The source code is available at in http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/pub/frame99/RTFlow.zip.† This application requires the Microsoft Vision SDK and a supported frame grabber (e.g., Matrox Meteor II).† The application computes image flow on 160x120x24 input images, and displays the results in real-time (30 FPS with NTSC input).

6 Hard real-time extensions to Windows NT

For more demanding real-time systems, there are several hard real-time extensions to Windows NT.† Some of these extensions replace NTís hardware abstraction layer (HAL) with a new HAL, while others are separate kernels running simultaneously with NT on the same system, and communicating through events and shared memory.† A few of the hard real-time extensions to Windows NT are listed below:

- Realtime ETS Kernel, http://www.pharlap.com/

- iRMX, Falcon http://www.radisys.com/

- LP-RTWin Toolkit, http://www.lp-elektronik.com/

- VENIX/386, RTX 4.1, http://www.vci.com/

- HyperKernel, http://www.imagination.com/hyperker.html

In addition to these extensions, Microsoft is provides Windows NT Embedded, which can be used for embedded applications (though the underlying OS is still not hard real-time).† Also, the currently available Windows CE 2.0 includes many hard real-time OS features that Windows NT lacks.

7 Conclusions

In this paper, we have discussed many of the important issues involved in developing real-time computer vision applications.† The Intel Pentium III and Windows NT provide a good platform for many types of real-time vision applications.† It is no surprise that to achieve maximal performance, you must understand the architecture and program for it.† However, the performance benefits often outweigh the extra cost of design and implementation.

8 References

1.††† Cutler, R. and M. Turk. View-based Interpretation of Real-time Optical Flow for Gesture Recognition. in IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition. 1998. Nara, Japan. http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/pub

2.††† Jones, M.B. and J. Regehr. The Problems You're Having May Not Be the Problems You Think You're Having: Results from a Latency Study of Windows NT. in Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems. 1999. http://www.research.microsoft.com/~mbj/papers.html

3.††† Timmerman, M., Windows NT as Real-Time OS?, in Real-Time Magazine. 1997. http://www.realtime-info.be/encyc/magazine/97q2/winntasrtos.htm

4.††† Ramamritham, K., et al. Using Windows NT for Real-Time Applications: Experimental Observations and Recommendations. in IEEE Real-Time Technology and Applications Symposium. 1998. http://www.merl.com/reports/TR98-02/index.html

5.††† Microsoft Developer Network. 1999. http://msdn.microsoft.com

6.††† Cutler, R., Meteor2Capture. 1999. http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/software/Meteor2Capture

7.††† Cutler, R., DiskBench. 1999. http://www.cs.umd.edu/~rgc/software/DiskBench

8.††† Intel, Intel 440GX AGPset Product Overview. 1998. http://www.intel.com/design/chipsets/440gx

9.††† Intel, Intel Architecture Software Optimization Reference Manual. 1999. http://developer.intel.com/design/PentiumIII/manuals/

10.† VTune. 1999, Intel. http://developer.intel.com/vtune/analyzer/

11.† Cutler, R. and L. Davis. Real-Time Periodic Motion Detection, Analysis, and Applications. in Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 1999.

12.† Intel, Application Note: Using MMXô Instructions to Implement Data Alignment. 1996. http://www.intel.com/drg/mmx/appnotes/ap576.htm

13.† Intel, Application Note: Data Alignment and Programming Issues for the Streaming SIMD Extensions with the Intel C/C++ Compiler. 1999. http://developer.intel.com/vtune/cbts/strmsimd/833down.htm

14.† Booth, R., Inner Loops: A sourcebook for fast 32-bit software development. 1997.

15.† Fog, A., How to optimize for the Pentium family of microprocessors. 1999. http://www.agner.org/assem/pentopt.htm